Books

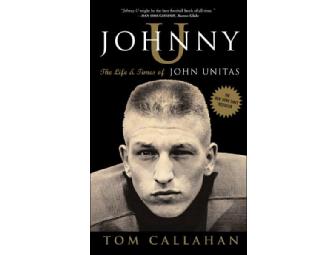

Johnny U: The Life and Times of John Unitas (Hardcover) by Tom Callahan (Author)

- Item Number

- 987823

- Estimated Value

- 25 USD

- Opening Bid

- 8 USD

Item Description

From The Washington Post

Tom Callahan's affectionate account of the life and times of Johnny Unitas isn't so much a biography as an informal portrait, and it really is as much about the times as it is about the man, or, as he says, "less about a specific place in the country than a place where the whole country used to be." Unitas joined the Baltimore Colts of the National Football League in 1956, when professional football still existed at the periphery of American sports and when the money was anything except big. Callahan writes:

"The time was different. The players lived next door to the fans, literally. There wasn't a financial gulf, a cultural gulf, or any other kind of gulf, between them. Except for a dozen Sundays a year, the Colts were occupied in the usual and normal pursuits of happiness. 'I remember when Alan and I bought our first row house,' Yvonne Ameche said. 'We paid eight thousand dollars for it. John Unitas came over and laid our kitchen floor. Everyone pitched in, painted and helped us get that little row house ready.' . . . In an annual visit to every locker room in the league, the Philadelphia-based commissioner of the NFL, DeBenneville 'Bert' Bell, emphasized the virtue of community. 'He told us,' [one Baltimore player] said, 'that if you're going to play professional football in a town, you have to live in that town, really live there. "Otherwise," he said, "don't play." A lot of us took that to heart.' "

Nobody could have known it at the time, but huge change was only a couple of years away. The decisive moment occurred in December 1958, when Unitas and the Colts defeated the New York Giants for the NFL championship in an overtime game for which the only appropriate adjective was, and remains, thrilling. I remember it as though it had just happened. I was 19 years old, at home from college for Christmas vacation, bored to the point of comatose. The school where my father was headmaster had a black-and-white television set in its recreation room, to which I retreated in desperation the afternoon of Dec. 28. I knew nothing about pro football when the game began and was hooked on it for life when it ended.

So too were millions -- literally, millions -- of other Americans. Callahan quotes the great Baltimore receiver Raymond Berry: "I remember seeing Commissioner Bell standing in the back of our locker room after the game. He was crying. I think he knew what we didn't -- yet. That this was a watershed for the NFL." A former Colt named Don Shula, who by then was an assistant coach at the University of Virginia, said: "That's the game that changed professional football. The popularity of it started right there."

This alone would be reason enough to celebrate Unitas, who was the dominant figure on the field that day: " 'Twelve players from that game went on to the Pro Football Hall of Fame,' said [New York linebacker Sam] Huff, who was one of them. 'Twelve players plus [Vince] Lombardi, [Tom] Landry, and [Weeb] Ewbank. Fifteen Hall of Famers on the same field. And one master. Unitas was the master.' " Indeed he was. Most people who know what they're talking about say he was the greatest quarterback in the history of the game, though partisans of Sammy Baugh, Otto Graham, Joe Montana, John Elway and a few others can muster strong arguments. He wasn't smooth or pretty, but he had remarkable peripheral vision, an (again to quote Berry) "amazingly organized mind, a fabulous memory," bottomless toughness and self-discipline, and a natural capacity for leadership. Lenny Lyles, another teammate, said: "He had character. He wasn't the All-American-looking quarterback like out of a movie. He had it inside."

He was born and raised in Pittsburgh. Callahan is scarcely the first to make the point, but Pittsburgh and Baltimore were mirror images of each other in those days: hard as steel (which both of them manufactured) but surprisingly soft inside, cities made up of discrete and self-contained neighborhoods, proud but modest. Another very good quarterback who came out of western Pennsylvania, Jim Kelly, speaks of the local "work ethic that says, 'What you get out of something depends on what you put into it,' " which could just as easily be said of Baltimore. When Unitas got there he fit in naturally and immediately, and the city embraced him as its favorite son. In all of Baltimore's greatest sporting years, the 1960s and '70s, only one other athlete stood as tall there as Unitas: Brooks Robinson, the Orioles' third baseman from Arkansas, whose down-home character mirrored Unitas's but with a Southern accent.

The story of how Unitas got to Baltimore is well-known. He played football at the University of Louisville -- he was a good Catholic boy who always wanted to play for Notre Dame but was told he was too small (5 feet 11) -- and was drafted, probably rather reluctantly, by his hometown NFL team, the Steelers, who scarcely gave him a chance during the exhibition season and cut him when it was over. He played semi-pro ball for a while, then was invited to try out for Baltimore. The Colts had been mediocre for years, but within little more than a single season Unitas had turned them into one of the most powerful teams of the day.

He had more than a little help from his friends: Art Donovan, Lenny Moore, Raymond Berry, Eugene "Big Daddy" Lipscomb, Alex Hawkins, Jim Parker, Alan Ameche, Jim Mutscheller, John Mackey and, above all, Gino Marchetti, the nonpareil defensive end. If Unitas was the heart of the team, Marchetti was its soul; maybe, as Lenny Lyles suggests, he was both. By the standards of the late 1950s and early '60s, the Colts were relatively free of racial tension, but black and white players mostly went their separate ways, united on the field but racially divided off it. Lenny Moore, who is African American, told Callahan about a conversation he had with Ameche, who was known as the Horse, at a gathering after their playing days were over:

"The Horse and I were just standing there. I could tell he wanted to say something, but it took him a while to get it out. 'Lenny,' he said finally, 'the black players on our team were treated very unfairly in the glory years. I want you to know it bothered me then, more than anything in my career, and it has bothered me ever since. And what bothers me the most is, I never did a thing about it.' He said, 'I don't know what it was that held us together, that allowed us to do all those great things on the field.' "

"I don't know either," Moore said to Callahan, "but I think it was something inside Gino Marchetti." True enough, but with more than a bit of John Unitas thrown in.

Unitas played for the Colts for more than a dozen years -- a very long time, by pro-football standards -- but his last seasons were diminished by injuries and age. He wasn't a factor in the second-most-important pro-football game ever played, the Colts' 16-7 loss to the New York Jets of the American Football League in 1969, in the third Super Bowl, the game that left no doubt the young AFL could hold its own against the established NFL and thus opened the way for the successful -- and wildly lucrative -- full merger of the two leagues in the early 1970s. Unitas played out his career in San Diego, but never felt at home in that warm, sun-washed city and beat it back to Baltimore as soon as he could. He stayed there, a beloved civic monument, until his death four years ago.

Callahan, whose long career as a sportswriter includes a stint about a decade and a half ago at The Washington Post -- I have no recollection of crossing his path in its corridors -- graciously and gracefully pays Unitas the tribute due him without lapsing into sentimentality. He does have one odd and, to my taste, unappealing tic: He repeatedly refers to himself not in the first person but as "the sportswriter," as in, "On the way out, the sportswriter encountered . . .," and, "Nicklaus told the sportswriter. . . ." If this mannerism is intended to put the author in the background, it actually emphasizes his presence, which is unnecessary to the telling of Unitas's tale and diminishes what is otherwise a very good book.

Copyright 2006, The Washington Post. All Rights Reserved.

Item Special Note

Winner needs to pick up the book by December 14th at the Foundation Office in Building 600 on Campus.

Donated By:

Solano Community College Foundation stores data...

Your support matters, so Solano Community College Foundation would like to use your information to keep in touch about things that may matter to you. If you choose to hear from Solano Community College Foundation, we may contact you in the future about our ongoing efforts.

Your privacy is important to us, so Solano Community College Foundation will keep your personal data secure and Solano Community College Foundation will not use it for marketing communications which you have not agreed to receive. At any time, you may withdraw consent by emailing Privacy@frontstream.com or by contacting our Privacy Officer. Please see our Privacy Policy found here PrivacyPolicy.